This post is part of a series on the Saints in Protestant Spirituality. You can read the introduction here, a bit on the Bible’s concept of sainthood here, and approaches to honouring the saints in Protestant confessions here (Church of England), here (Lutheran) and here (Swiss Reformed).

So far we’ve only talked at a theoretical level about saints’ days. We’ve looked at the idea of saints in the Bible and heard what the Protestant Reformers had to say about the kind of honour that was (and wasn’t!) to be given the saints. In this post we’re going to look at what that translated to concretely in the Book of Common Prayer, the liturgy of the English Reformation.

Saints’ days in the BCP come in two flavours; so called ‘red letter’ days and ‘black letter’ days. I’m given to understand that this distinction came from the way different classes of festivals were noted in medieval calendars. More significant festivals were marked out in red, while less significant ones were left in black. I own about 10 different copies of the BCP printed over the course of the last 170 years and have never seen anything but black ink. Nevertheless, the name persists and what with printing in colour being both easier and cheaper than it was in Tudor times, the calendar in Common Worship has returned to a red/black split.

Red Letter days

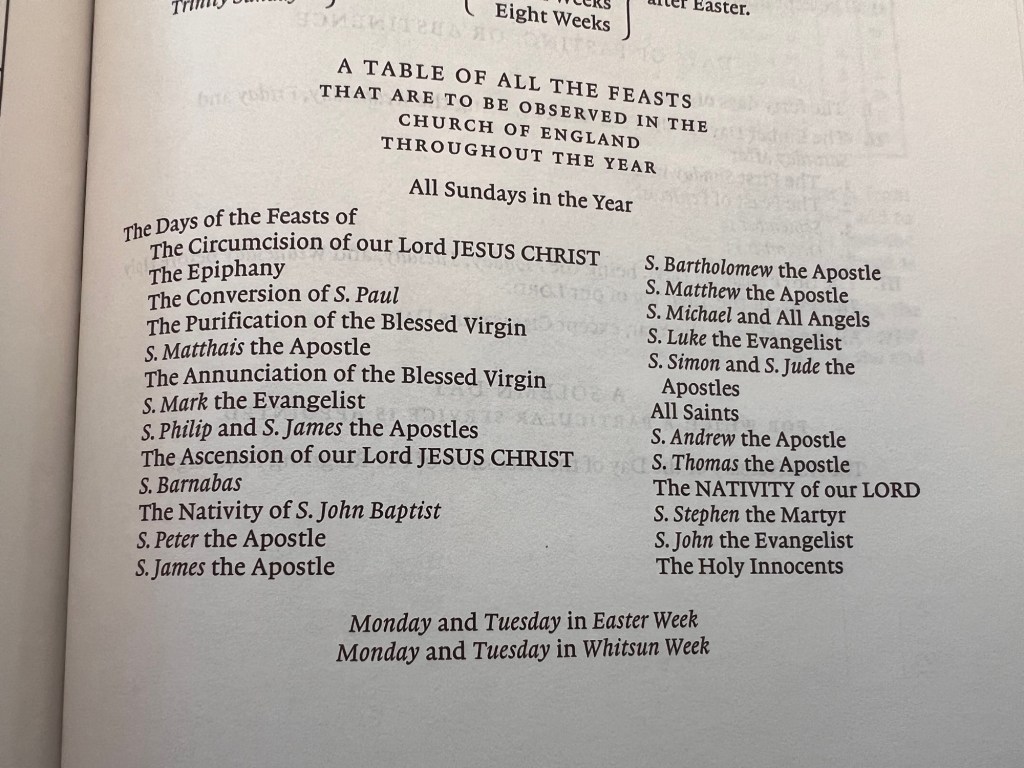

In addition to what you might call the dominical feasts (Christmas, Easter Pentecost etc), the Prayer Book contains about 20 red letter days which commemorate saints.1 In practice, this means that the average month contains one or two of them. That represents a drastic reduction in number compared to before the Reformation, based on a desire to disrupt the consecutive reading of Scripture as little as possible.

All the red letter days commemorate people found in Scripture. I doubt that anyone in the Tudor church doubted the salvation of Church Fathers such as Augustine or John Chrysostom for a moment, but when it comes to the public worship of the Church, the Reformers clearly wanted to limit it to people we know from Scripture played a role in preserving and passing on the Gospel.

What that leaves you with is the twelve Apostles (no, there’s not a day for Judas Iscariot, but there is one for Matthias!), Paul (well, his conversion at least), Barnabas (because he appears to be referred to as an Apostle in Acts 14:14), Mark and Luke (so that we get all four evangelists), John the Baptist, Stephen (because he is the first martyr) and St Michael and all angels. Two festivals (the feast of the presentation/purification of the Blessed Virgin and the annunciation of our Lord/the Blessed Virgin) could be classed as either Dominical or Marian depending on what angle you look at them from (both is best!). And then, of course, there is All Saints’ Day.

The Prayer Book not only limits its liturgical provision to Biblical figures, it also strictly limits itself to things Scripture itself says about them. There are a great many sayings, traditions, legends from the early church about the activities of the Apostles which range from things which are almost certainly true (e.g. that Peter and Paul were both executed during the Neronian persecution) to things which are wildly implausible. Sometimes the calendar presupposes traditional exegetical decisions about the identities of various figures.2 Some of these are a little contestable3, but even if you happen to think the calendar has merged two people into one there is still nothing legendary included in the liturgy.

This means that several of the days are extremely muted. Frankly, Scripture hardly tells us anything about most of the Apostles and the Prayer Book does nothing to fill in the blanks. One thing Scripture does say is that, in ways presently unknown to us, they each played their part in ensuring that the teaching of Jesus made it to us intact. You don’t get your name written on the foundations of the New Jerusalem’s walls (Rev 21:14) for nothing! And for that we are immensely thankful – think how devastating it would be if they had not.

Each day is marked out by three things:

- Each day has its own collect. If you’ve read almost any other post on Christ and Calendar, you’ll be familiar with the collects. Essentially, they are a short prayer (usually one sentence long) themed to the day. On a festival day everything else about Morning and Evening Prayer is exactly the same as usual except that this collect will be particular to the day.

- Each day also has ‘proper’ readings. ‘Proper’ here doesn’t mean they’re the correct readings, as if anyone who reads anything else is doing it wrong, it means they’re the readings that belong to this festival (like ‘property’). If it’s a figure about whom the New Testament says a lot, these will usually be some of the salient moments in that person’s life. If not, they tend to be readings which point more broadly to the way that the Apostles and Prophets received and passed on God’s word, and to the fact that all God’s word centres on Jesus.

- The day before is designated a day of fasting or abstinence and a vigil is traditionally kept the evening beforehand (hence names like Christmas Eve or All Hallow’s Eve). There’s nothing in the Prayer Book to tell you how to keep a vigil, so I’ve always assumed that is up to the individual, except that the collect of any feast day is used on the evening before (except for Christmas Eve and Easter Eve, which both have collects of their own)

This is all very pruned back from the pre-Reformation norm. In the previous post we saw that in the Second Helvetic Confession, Bullinger decried the many things ‘absurd and useless’ which attended saints’ days. He doesn’t elaborate on what he means by that, but I think the Prayer Book festivals, purified as they are of legendary material, pageantry, and the veneration of saints, relics and icons, are manifestly exempt from that charge.

Black Letter days

In addition to the red letter days, there are a number of black letter days (about 60 or so) listed in the BCP calendar. These appeared suddenly in the Elizabethan period for reasons that are now a bit obscure.4

Many of these days are also named after a saints, though some of them (such as the transfiguration) are not. Most of them are either major figures in the early church, prominent martyrs, or people who played an important role in bringing the Gospel to England and Wales. There’s no liturgical provision for any of them, so unless someone wished you a happy St Etheldrede’s Day on the way into church, you could get through the whole Prayer Book service without ever finding out.

It seems likely that the people who first added these days into the calendar simply intended them to be a way to mark time. Nonetheless, they do serve the purpose of keeping the memory of some key saints alive and if you looked them all up, you would get at least a tolerable picture of how the Gospel made it to this country. These days most churches that use the Prayer Book in public worship include a time of intercessions in addition to the set prayers and you might find that – depending on the person making the intercessions and the saint whose day it is – some mention is made in these prayers.

For all the saints

In the second post of this series, we saw that when we talk about ‘the saints’ we’re usually using that word as a shorthand for a concept which is Biblical but doesn’t generally go by that name. When the Bible refers to saints, it’s referring to all God’s people. It’s important that we honour that and there are a few ways in which the Prayer Book, taken as a whole, does so. In fact, when you realise just how often this broader understanding of the saints features in the day to day, it becomes obvious that references to the Biblical understanding of sainthood far outnumber the more restrictive use connected to saints’ days. These also give us an angle on how the saints feature in our day to day and not just on special occasions.

The most obvious place the saints pop up is in the Creed. Twice every day, at morning and evening prayer, the Prayer Book has us recite the Apostles’ Creed. In doing so we confess, day by day, our faith in the Communion of the Saints. That isn’t a reference to a spiritual elite, but to the fellowship that all Christians have with one another and the status as saints that we have before God through the work of the Holy Spirit in uniting us to Christ.

Beyond that, in the morning we say either the Te Deum or the Benedicite. In the former, we praise God as we call to mind the worship of the saints and the angels in God’s throne room and include ourselves in that:

All the earth doth worship thee, the Father everlasting.

To thee all angels cry aloud, the heavens and all the powers therein.

To thee cherubin and seraphin continually do cry,

Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth;

Heaven and earth are full of the majesty of thy glory.

The glorious company of the apostles praise thee.

The goodly fellowship of the prophets praise thee.

The noble army of martyrs praise thee.

The holy Church throughout all the world doth acknowledge thee:

And we address Christ in prayer saying

We therefore pray thee, help thy servants,

whom thou hast redeemed with thy precious blood.

Make them to be numbered with thy saints in glory everlasting.

For me this is all very reminiscent of the ‘ardent longings’ and earnest supplications mentioned in the Second Helvetic Confession. We express our desire to join with the saints, to be with them and to rejoice with them in Christ in glory. And again, we are not asking about a small elite, but all those who are sanctified through Christ’s redemptive work on the cross.

The Benedicite, which is a prayer which, in the style of Psalm 148, calls on the whole creation to praise the Lord, finishes by calling on the people of God to praise him:

O ye Children of Men, bless ye the Lord :

praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O let Israel bless the Lord :

praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O ye Priests of the Lord, bless ye the Lord :

praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O ye Servants of the Lord, bless ye the Lord :

praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O ye Spirits and Souls of the Righteous, bless ye the Lord :

praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O ye holy and humble Men of heart, bless ye the Lord :

praise him, and magnify him for ever.

The Benedicite was written before the coming of Christ, so it speaks in terms fitting to the people of God at that time, but it unmistakably calls the whole people of God – including the ‘spirits and souls of the righteous’ (c.f. Heb 12:22-24) – to praise him together as one holy fellowship.

The BCP’s service of Holy Communion likewise includes reference to the saints in the prayer for the church militant:

And we also bless thy holy Name for all thy servants departed this life in thy faith and fear; beseeching thee to give us grace so to follow their good examples, that with them we may be partakers of thy heavenly kingdom

This prayer combines the elements of thanksgiving and imitation which the Protestant confessions would lead us to expect in a Reformed prayer referencing the saints. And note the word ‘all’ there. All who have departed this life in the faith and fear of God are saints for whom we give thanks and who we seek to imitate.

The introduction to the Sanctus reminds us that we are praising God together with ‘angels and archangels and with all the company of heaven’, once more drawing our worship into that of the saints and angels. After communion, one of the optional prayers thanks God for assuring us that

we are very members incorporate in the mystical body of thy Son, which is the blessed company of all faithful people; and are also heirs through hope of thy everlasting kingdom, by the merits of the most precious death and passion of thy dear Son. And we most humbly beseech thee, O heavenly Father, so to assist us with thy grace, that we may continue in that holy fellowship, and do all such good works as thou hast prepared for us to walk in; through Jesus Christ our Lord,

And of course, there is All Saints’ Day tomorrow – a day devoted to celebrating the ‘one communion and fellowship in the mystical body of [God’s] Son’ into which we have been knit – more on that tomorrow.

The Prayer Book of the English Reformation, then, incorporates the saints into its worship in a way which is, on the one hand, sober and scriptural and on the other, pervasive and mystical. If we take its prayers seriously, the reality of the saints and the wonder of our inclusion in their number, is a reality that is to be frequently in our hearts and on our lips adding joy and holy fear to our praises and a new dimension to our sense of self.

The next post in our series will look at a few tips for how you might make a start observing the saints’ days in the BCP calendar.

Post Script: Common Worship

Common Worship, the new set of liturgies prepared for the Church of England in the year 2000 massively expands on the calendar. Some of this is for the good. There are a few more biblical figures, including Joseph and Mary Magdalene, which I think adds something helpful. There are tonnes more black letter days, now divided into two categories, one of which gets an optional collect and the other of which does not. Like most of Common Worship, it’s a ‘choose your own adventure’ job and you’re not obliged to use any of this new material. The new black letter days are undeniably a mixed bag, with some valuable Reformation and Post Reformation additions (Christianity did not stop in the 16th century, after all) and some others who I would not have chosen to add. As an occasional user for Common Worship, it all feels rather clogged up to me and it’s almost a surprise when I discover that the day isn’t a commemoration of some sort.

- The precise number depends on things like whether you count the Archangel Michael as a saint, or whether the massacre of the innocents is about an event in Christ’s life or the children who were killed. I’m not here to split hairs. ↩︎

- e.g. that John the son of Zebedee is the same person as the author of John’s Gospel, or that the Apostle known in the synoptics as Bartholomew is known as Nathaniel in John’s Gospel. ↩︎

- Traditionally, the church has treated James the Son of Alphaeus, James ‘the lesser/shorter’ and James the kinsman of the Lord as being the same person. Personally, I’m of the view that the Son of Alphaeus is a separate individual, but James the less and the kinsman of the Lord are one and the same. As it happens, the ACNA calendar follows this interpretation, giving James the Kinsman of the Lord a separate feast day of his own. ↩︎

- For a helpful discussion of this, see this article. ↩︎