Merciful Lord, we beseech thee to cast thy bright beams of light upon thy Church, that it being enlightened by the doctrine of thy blessed Apostle and Evangelist Saint John may so walk in the light of thy truth, that it may at length attain to the light of everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Book of Common Prayer

By comparison with St Stephen, there is something intuitively Christmassy about St John.1 Whether as the climax of the nine lessons and carols, or the Gospel reading in the Christmas day service, or the basis of one of your Advent quiet times, it would probably take a concerted effort to avoid hearing the prologue to John’s Gospel at some point in the festive season.

All of the evangelists communicate their belief in Jesus’ divinity in one way or another, yet Christians have always held that John teaches it with a special clarity. It is, from the very beginning, a focal point on which John focuses his contemplation.

John’s Gospel is often associated with a certain mysticism. That’s a word many evangelicals are uncomfortable with, rightly wary of experiences of God unmoored by Scripture. But it’s appropriate for John, as he draws us to reflect on Jesus’ miracles as ‘signs’. Hidden beneath the outward appearance (awe inspiring enough) of events like water made wine, paralytics healed, the blind given sight, the dead raised are rich patterns of Scriptural allusion and symbolism that intimate, to those with eyes to see, the presence of a new and glorious reality bursting into the present world. It is John’s Christology that most overtly wrestles with the paradox of God made flesh, present with his people but unrecognised by them. It is John who insists that Jesus’ death, a grotesque picture of wretchedness in the ancient world, is the place where his glory is simultaneously hidden and revealed.

John is fundamentally the apostle who saw the Lord. Not only is his Gospel the one which makes the most repeated and overt claims to eyewitness testimony, he also describes what he saw in terms which evoke and yet relativise all previous visions of the Lord. ‘No one has ever seen God’, John tells us. Not really. On St John’s day, the lectionary points us to Exodus 33 – the paradoxical passage where Moses speaks to God ‘face to face’ in the tent of meeting and yet, when he asks to see God’s glory is told that he cannot see God’s face and live. John by contrast says that ‘the word was made flesh and pitched his tent among us and we have seen his glory’. The lectionary points us to Isaiah 6 where Isaiah sees the Lord ‘high and lifted up’. By a complex web of intertextual allusions, John tells us that the vision of divine glory in Isaiah 6 and the vision of the suffering servant ‘high and lifted up’ in Isaiah 52:13&53 are in truth one and the same, that of the Son of Man ‘lifted up’ on the cross, to which he was an eyewitness (c.f. John 12:20-end).

Even in his comparison between Peter and John in chapters 20-21, John is the Apostle who always seems to see just a little farther (even while admitting that Peter loved more ardently). There is a fittingness to the manner in which John lives the longest, guiding the nascent Church as the Elder2, and is ultimately granted his mysterious vision of the last things.

If St Stephen’s day jars us out of the twee sentimentality that sometimes surrounds the Christmas season, St John reminds us that while the Christmas story is simple enough that it has entertained our children in nativity services these last few days, there are hidden depths which an eternity of contemplation will not fathom, glories which make visible what lay out of reach even to the greatest of the prophets of old.

To go from the sublime to the ridiculous, an apocryphal tradition says that St John was once given poisoned wine, which he drank without being harmed. From this arose the tradition, common up until the Tudor period, of drinking wine on St John’s day.3 We made sure to have our first mulled wine of the season today. Cheers!

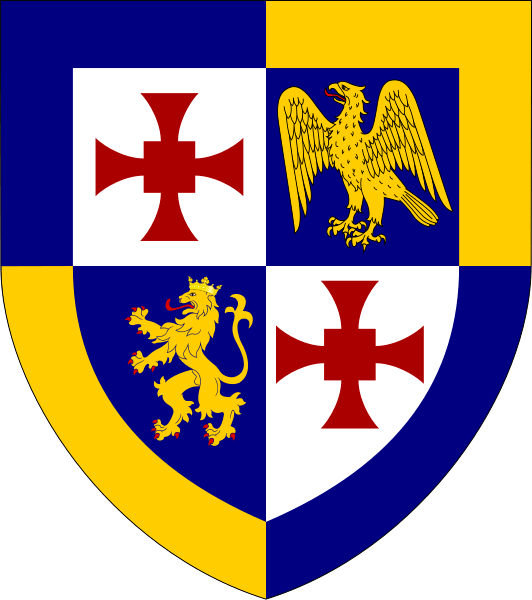

The image for this post is the coat of arms of St John’s College, Durham, where I spent four of the happiest years of my life.

- For the sake of clarity, the calendar assumes that John the son of Zebedee, John the Evangelist, John the Elder, John the Seer and the beloved disciple are all the same person. I know an ocean of ink has been spilled over this (I had to read some of it at college) but in my view this approach is still probably the best and will be assumed throughout this post. ↩︎

- John’s great age makes him the last link between the apostolic age and the earliest church fathers we have written remains from, such as Ignatius of Antioch and Polycarp of Smyrna. ↩︎

- For this and a million and one fun Tudor Christmas facts, check out Alison Weir and Siobhan Clarke’s A Tudor Christmas – which is an absolute favourite of mine at this time of year. ↩︎